When it comes to bonds, the two most common ways to increase return are through credit quality and maturity. Lower credit quality bonds offer higher rates to offset the higher risk that the issuer will default. Most bonds are assigned a credit rating, and that rating corresponds to the risk that the issuer will default - fail to pay interest or return principal - on a given bond.

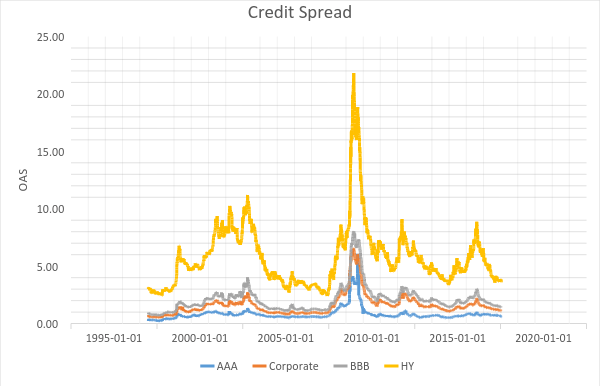

Bonds that have the same credit rating will - all else equal - offer the same interest rate, and that rate will be above the interest rate offered for issues with a better credit rating. You may have heard the term “credit spreads” before, and the spread is the difference in interest rates between, for example, U.S. Treasuries and high grade corporate bonds.

While the higher return for lower credit quality can be enticing, according to Moody’s, historically over 30% of non-investment grade bonds have defaulted while only 2% of investment grade issues have done the same. Credit spreads fluctuate constantly, offering an indirect measure of investor sentiment and they also provide a clear illustration of the trade-off between risk and return. The chart below shows credit spreads over the last 20 years for different types of bonds - note that HY in the chart is high yield, or non-investment grade bonds.

Chart 1 - Credit Spreads

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BAMLC0A1CAAA

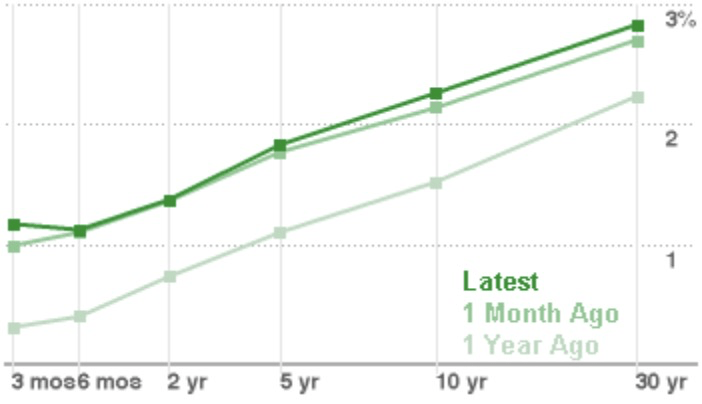

Aside from taking on credit risk, purchasing longer-term bonds is another way of increasing return. Financial theory tells us that investors require higher returns for longer holding periods. We can actually measure how much more return investors require in aggregate by looking at the yield curve, which is below. The yield curve shows the return offered by the same type of bond as maturity varies and most of the time, the curve shows that the longer the maturity, the higher the rate paid.

Chart 2 - Yield Curve

Source: TD Ameritrade Research

The problem with using cash reserves or short-term cash to invest in longer-term bonds is that there is a good chance you won’t hold them until maturity. Holding to maturity is the only way to ensure you’ll receive the face value of the bond when you sell it. When you sell a bond prior to maturity, interest rate risk becomes a factor.

Interest rate risk is the risk that rates will increase and as a result, prices of existing bonds - like the bond you’re planning to sell prior to maturity - will drop in value. Duration is a measure that tells you how much the price will drop for a given bond if interest rates increase (or conversely, how much the price will rise if rates decrease). A bond with a duration of 5, for example, will see a price drop of roughly 5% if interest rates increase by 1%.

One last risk to consider in purchasing a bond with funds intended for the short-term is liquidity risk. Liquidity risk is the risk that you either won’t be able to sell a bond or that you won’t be able to sell the bond without driving down market prices. Some bonds are very thinly traded — some municipal bonds, for example, go days or weeks without being traded and when they are traded, offers are scarce and poorly priced.

There are other risks associated with bonds, but the three discussed above are the primary short-term risks. We try to minimize risk for emergency and short-term funds, but if you are intent on earning higher returns for this portion of your portfolio, make sure you understand the risks.