If you’ve followed the news about the new tax bill, you may have noticed that in an attempt to answer the question “Will it save me money?” writers are resorting to offering a varied group of hypothetical tax payers. The reason for this is that the bill changed a number of different aspects of the tax code, and many of those changes work at cross-purposes if the purpose is lowering your tax bill. It should help most individuals, at least in the initial years but there is significant variation. Furthermore, if we widen the frame to include secondary impacts of the new bill, the question becomes even more difficult to answer.

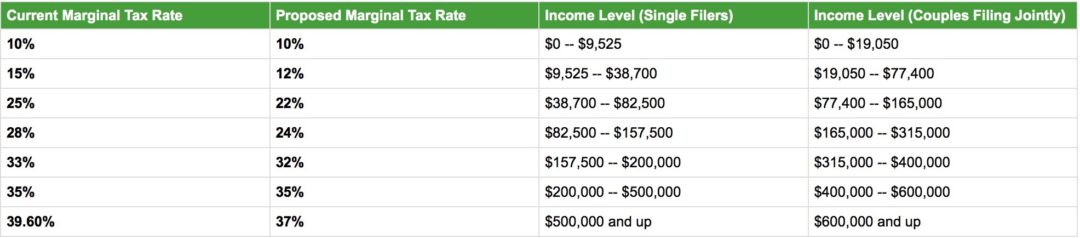

When it comes to decreasing what individuals will pay under the new bill, lower tax rates are responsible for a good bit of the impact. As you can see from the table below, tax rates are decreasing across all tax brackets.

The increase in the standard deduction will also help the nearly 2/3rds of taxpayers who don’t itemize their deductions. On the negative side, the bill removed personal exemptions and limited or eliminated a number of deductions including those for state and local taxes (including property tax), home equity mortgage interest, and miscellaneous itemized deductions. The upshot of this is that if your deductions were well in excess of the standard deduction, you may find little to no tax reduction under the new tax bill.

The legislation will have impacts beyond simply what you owe in taxes. One of the most notable impacts is the removal of the individual mandate to purchase healthcare. The mandate required nearly everyone to have health insurance, and removing the mandate makes it likely that some healthy individuals will elect to go without coverage. This will, in turn, lead to a less healthy insured population and insurers will raise rates to account for this. How much premiums will increase is a source of debate among experts, but if you have individual coverage and aren’t eligible for subsidies, increasing premiums should be weighed against any tax savings.

The new tax bill could also impact Medicare and other government programs due to what are known as Paygo rules. Paygo is short for “pay-as-you-go”, and they are budgetary rules that require that any change that drives up the deficit must be offset. The new tax bill is estimated to run a deficit of $1.5 trillion over 10 years, with $175 billion of that increase occurring in 2018. To offset part of the deficit, Medicare spending was slated to be cut by $25 billion in 2018 until Congress voted to waive Paygo. They will have to continue to do this for the duration of the 10 year window to avoid automatic spending reductions.

One final indirect impact that is, at this time, difficult to judge is the fact that this legislation is forecast to increase national debt by $1.5 trillion. Debt currently stands at a bit over $20 trillion and absent unlikely offsetting cuts via Paygo, the tax bill will add about 8% to that figure over 10 years. At some point – absent any plan or apparent inclination to decrease our debt – it is likely that investors will demand higher rates on U.S. government debt. How this plays out and what impact it has on investment portfolios is difficult to say but it does inject additional uncertainty over the next decade.