One of my favorite charts on investing is the Callan table of investment returns. The chart depicts the return of various asset classes1 from year-to-year, and just a glance at it shows how volatile relative returns can be. An asset class that leads the pack for several years may well drop to the bottom, as large cap growth stocks did around the turn of this century (who could forget the dot.com bubble?). One other thing the chart makes immediately clear is how random the movement among asset classes seems to be, and by extension, how difficult it is to predict the movement.

I find a need to dust off the Callan table when the U.S. markets have outperformed other markets over an extended period. The U.S. press focuses overwhelmingly on the U.S. stock market when discussing “market performance”, so most investors anchor expectations around those returns.

However, a diversified portfolio should include a good bit more than just the large cap U.S. stocks we hear about every day. When those same stocks outperform most other asset classes, the return of a diversified portfolio will seem lackluster by comparison.

We’ve been going through a period of U.S. outperformance over the last several years, especially when returns are compared to foreign stocks. Emerging market stocks, in particular, have had a rough go of it, and seemingly every month brings another story of an emerging market economy or market in turmoil. Emerging market stocks are supposed to be high flyers, outperforming stocks in more developed, slow-growing markets, so how does what we’ve seen over the last several years compare historically? Does it still make sense to invest in emerging markets?

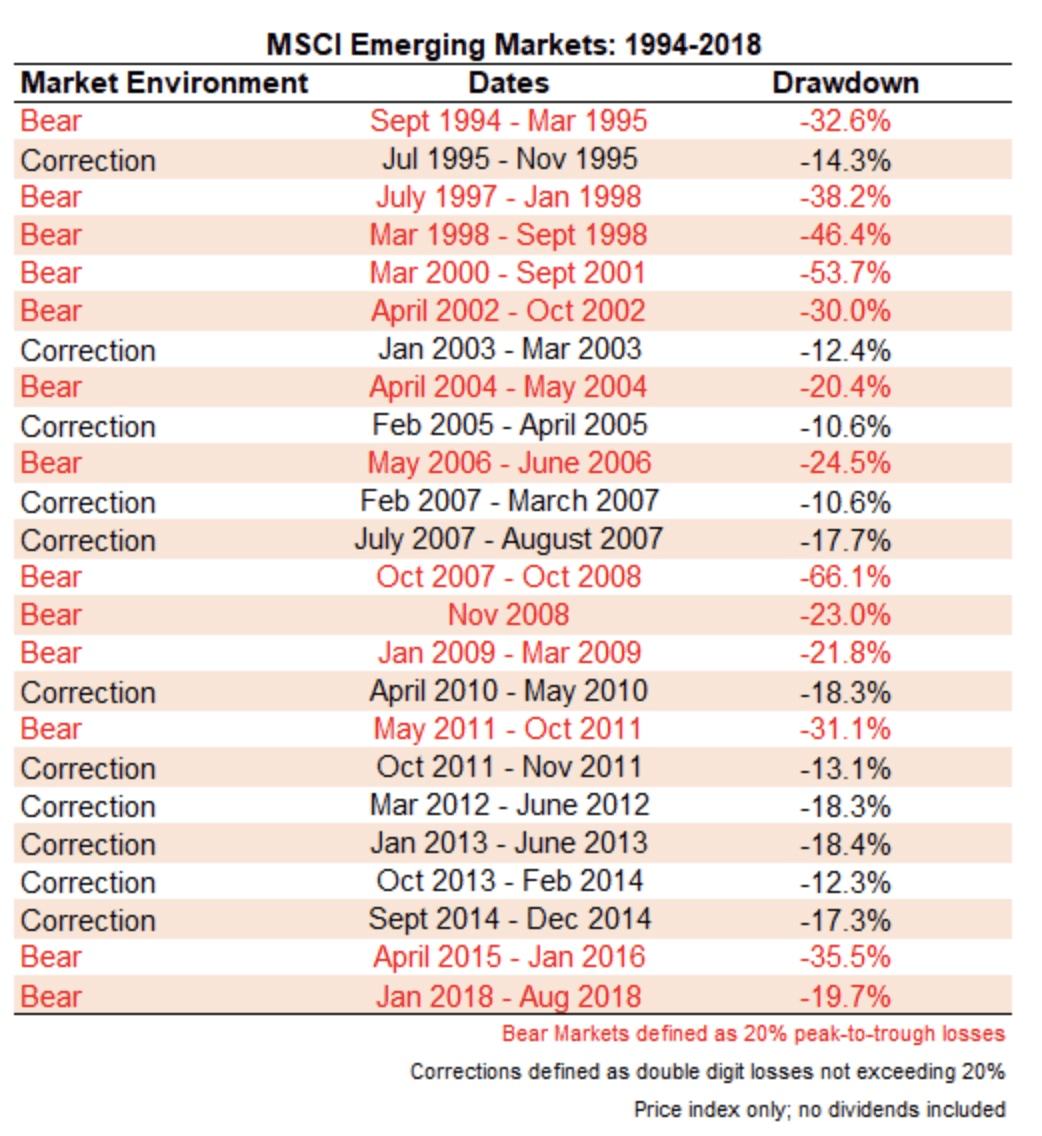

Ben Carlson recently wrote a column on emerging markets, and he focused on returns after a sharp drop in those markets. As the table below from that column shows, there have been no shortage of drops in emerging markets over the last quarter century. Since 1994, there has been a bear market every other year in emerging markets while the figure for developed markets is just 1 year in 6 (a comparison Carlson makes in another post). In fact, there was a little noticed drop of almost 40% in the last 8 months of 2015.

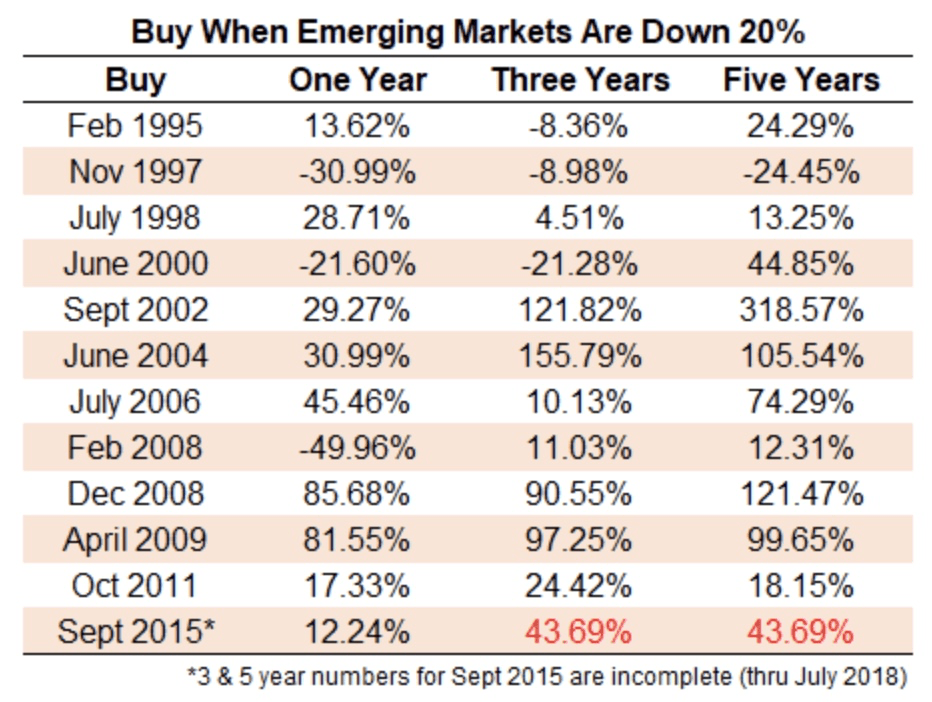

Nevertheless, over the last 30 years, the return of emerging markets has outpaced the S&P 500 return, and as the table below (again, from Carlson’s column) shows, the track record of returns 1, 3 and 5 years after sharp drops has been really good as well.

Overall higher returns are what one would expect given the volatility – but at any given point, emerging markets might be posting returns well below that of U.S. stocks. That is where investors find themselves thus far this year, based on historical performance, it would not be at all surprising to see a sharp rally that closes the gap between emerging markets and the U.S.

- Asset classes is a group of securities that have similar investing characteristics. For example, large cap value stocks might include large U.S.-based companies whose stocks are somewhat cheap when measured in terms of earnings. An asset class is different than a sector, which groups securities together based on the industry on which they focus. ↩