Years ago, before I became a financial advisor, I had a job that required me to fly a lot. I’d routinely log a few hundred thousand air miles a year, and somewhere along the way I developed a fear of flying. I cast about looking for ways to alleviate that fear, and I finally landed on the goal of learning everything I could about how planes worked. I could tell you about the sterile cockpit rule and why I didn’t usually hear announcements for the first few minutes after takeoff. I understood what went in to ETOPS testing so that twin-engine jets could safely cross great distances over oceans and the poles and I knew that if I was taking off from an airport at altitude, there was a good chance I’d be on a 757.

Even after everything I learned, I was still a nervous flyer. But I felt more comfortable because I understood what was going on – what the system was that safely thrust us skyward and held us aloft. And when something happened on a flight, some unexpected noise or missed approach and go-around, that knowledge allowed me to avoid a limbic-driven panic and instead think systematically about what was happening. It’s in that same spirit in which I write these posts. We’re in the midst of a once-in-a-century global pandemic, markets have dropped with unprecedented speed and there is no definite end in sight. But it is precisely at times like these that taking a step back, examining where things stand systematically and taking a long-term view are most valuable. So, with that in mind, let’s get started.

The Economy

The measures that Western countries have implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19 have slowed their economies dramatically, with the heaviest impact forecast to occur in the second quarter.

Goldman Sachs recently revised their Q2 GDP forecast from a decline of 5% to 24%. The economic impact of the virus is estimated to wane after the 2nd quarter, with 2020 GDP ultimately expected to come in at -3.8%. Whether the economy begins to recover after Q2 depends upon how effective efforts are to stem the spread of the virus, and fortunately there are examples of countries which have been successful. Stimulus is also going to play a key role, and I will discuss what we know so far on that front below.

Whenever the economy enters a downturn, stories begin to reliably appear about whether we’re heading for another Great Recession or even worse. We’re seeing those stories now, so I think it can be helpful to compare those events with what is currently forecast. Here is the relevant data:

The Great Recession – unemployment peaked at 10% in October 2009 with a total of 8.6 million jobs lost. Real GDP dropped 4.3% from the fourth quarter of 2007 to the 2nd quarter of 2009, and in addition to a number of Fed actions to stabilize markets, Congress passed a series of stimulus measures that totaled just under $940 billion.

The Depression – from 1929 to 1933, the Depression forced just under a quarter of able-bodied, working age Americans out of work. Over that period, GDP declined by 26.2%, and both the Fed and Congress took actions that worsened the downturn. Substantial fiscal stimulus finally arrived in the form of the New Deal in 1933 and the economy grew substantially for the next 4 years.

Covid-19 Recession – among the current economic forecasts we’ve seen, Goldman Sachs is the most negative. They currently forecast an economic decline for the year of 3.8% and unemployment peaking at 9%, though the latter figure would be materially impacted by the tools used within the pending stimulus package. The third package alone has a price tag of $2 trillion, or roughly 10% of the annual GDP, and will hopefully be focused on tiding us through the next few months.

One key difference worth reiterating about this downturn versus previous downturns is the speed with which it is happening. A key datapoint that is likely to drive this home is the weekly unemployment report covering initial unemployment claims. It will be released this coming Thursday, and odds are it will reach into the millions, the highest in the history of the report. If that does happen, it’s more a reflection of the steepness of the economic deceleration than of how deep the decline will ultimately be.

The Stimulus

The best explanation I have read about what is needed is from Larry Summers, who explains economic time has stopped, but financial time has continued. By that he means that from an economic perspective, the measures we have engaged to fight the pandemic have greatly reduced our ability to produce goods and services. Employees, or former employees, will go without salaries and businesses will earn no profit. Financially, though, bills don’t stop coming – there are utilities to pay, rent and mortgages to cover and so-on. The government can step in and provide direct cash payments to businesses and individuals to tide them through the next few months – essentially freezing things in place – so that after the spread of the virus wanes, those business and jobs are still there and the economy can slowly begin to get back up to speed as it has done in China.

A number of governments around the world have based their approach on these direct payments, essentially pledging to do whatever it takes to get through the next few months. The U.S. appears to be following the same path, although if it does take 3 months or more before we can return to normalcy, expect the price of the stimulus to climb well beyond the $2 trillion figure currently being quoted.

The Markets

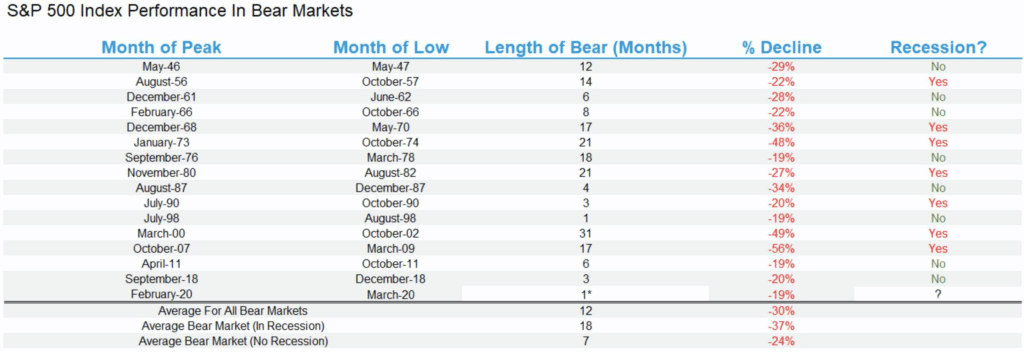

The unprecedented sudden decline in economic activity has driven a similar response in the markets. The drop of the S&P from its highs in mid-February to a year-to-date loss of nearly 30% is the swiftest decline on record. Most other markets are down as much or more, although thankfully very high credit quality corporate bonds and government bonds have done a good job of maintaining their value. The precise amount the S&P 500 is down through last Friday is 28.6%, and here is how that compares to prior downturns.

Source: LPL Financial and FactSet

A sizable percentage of the drop happened in the past week, and the VIX – often referred to as the market’s fear index – hit levels not seen since 2008. Such a high reading is typical of panic selling, and such selling often precedes a market bottom. Still, as I wrote a few weeks back, it seems likely investors will be at least as concerned with the spread of the virus and will need to see the spread slow before feeling confident about corporate earnings. While volatility may well decrease, a spike in the VIX isn’t a definitive sign the market has reached bottom. Once that happen though, what can we expect? Here’s chart of S&P recoveries from previous downturns.

Source: A Wealth of Common Sense

Portfolios

In bear markets, we turn to the most conservative part of portfolios to fund any cash needs you may have, so it is key that that portion of the portfolio holds its value. The investments that comprise the most conservative portion include any cash you may have along with 3 bond funds – FPA New Income, Metropolitan West and Double Line Total Return. Those funds have largely held their value (down between one and two percent since the beginning of the year) and assuming you’re drawing no more than 5% or so of your portfolio on a yearly basis, they should provide between four and eight years’ worth of funding, not counting any cash you also have in your portfolio. Running this back of the envelope calculation and comparing this to the length of previous downturns and recoveries helps us minimize the risk that you’ll have time for markets to recover, and not need to sell investments when they are down in value.

Bear markets also offer a few opportunities to investors, including tax loss harvesting. We’ll begin that process in the coming week, and that will result in lower portfolio-related taxes for 2020 and possibly future years as well. We’re not in the buy-the-dip mode yet but will begin doing that if the market declines further. Finally, we’re considering making some changes to smaller fund holdings including the Arbitrage Fund and T. Rowe Price Real Estate and Emerging Market Bond. If and when we move forward with those changes, we will let you know.

In the meantime, news over the next few weeks will likely be discouraging. The effects of recently-begun social distancing won’t be apparent immediately, and states will likely implement additional measures. Economic data will also begin to reflect the sharp downturn even as stimulus will take a bit of time to counter that impact. Whether the markets continue to react to every negative headline or tune it out as they find a bottom remains to be seen. This reminds me to some extent of where we found ourselves in early October 2008. The S&P had fallen over 30% from its highs, Congress had failed to pass TARP – the stimulus on the table at the time – in their first attempt, and investors were just coming to grips with the idea that the global financial system had come dangerously close to collapse and was still teetering.

It wasn’t an easy time to be an investor then, and it’s a challenging time now. One key difference though is that the problem now is much clearer and the timeframe between onset and aftermath is much more compressed. We’re here (working remotely and maintaining social distance), and given the need for good financial advice in times like these, we’re offering a complimentary retirement checkup – including a portfolio review. If you think that might be of help to you, you can learn more about the offer and sign up for your review here.